Dr Kenneth J Moise Jr., MD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Professor of Surgery

Baylor College of Medicine

Member, Texas Children’s Fetal Center

Texas Children’s Hospital

Houston, Texas

To download this booklet click Download Leaflet.

(This report is a PDF file, click here to Download the free latest version of Adobe Reader)

Introduction

Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia (NAIT) is a blood-related disease that affects expectant mothers and their babies.

Most people are familiar with the red blood cells that make up the majority of the blood in our bodies, but may not be aware of a second type of cell in our blood stream called platelets. These small cells are responsible for stopping bleeding in the human body.

Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia is a disease that develops when platelets in the pregnant mother and her baby become incompatible and cannot exist together.

The purpose of this booklet is to discuss the causes and treatment of Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia as well as to answer frequently asked questions about this disease.

1.How do platelet antigens, platelet alloimmunization and Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia relate to each other?

Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia is caused when the mother’s and baby’s platelets become incompatible, a condition known as platelet alloimmunization. To understand platelet alloimmunization, you must first understand about different platelet types. Platelet types are defined by antigens, substances or “factors” that exist on the surface of the cell. The most common of these is the HPA-1 antigen, which is present in 98% of people. These patients are referred to as HPA-1 positive. When their blood is tested, the test will return as HPA-1a/1a or HPA-1a/1b. About 2% of the population is HPA-1 negative; these patients are called HPA-1 negative. A blood test on one of these patients will return as HPA-1b/1b.

There are other platelet antigen systems found in humans that are associated with Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia, including HPA-3, HPA-4 (present in people of Asian descent), HPA-5, HPA-9 and HPA-15. If an antigen is present, the person is called positive for the antigen; if it is absent, the person is called negative for the antigen.

When a woman becomes pregnant, genes (inherited traits) from her egg are combined with genes from her partner’s sperm. Together a unique embryo (future baby) is formed. This embryo carries with it genes from both the mother and the father. These genes include things such as hair and eye color, body build, blood type and platelet type.

Platelet alloimmunization happens when a mother’s body forms antibodies (a protein substance that reacts to unrecognized proteins in the body) in reaction to antigens that are different from her own.

These antibodies are usually formed when the mother’s blood circulation comes in contact with blood from another person that is different from her own. This can happen with blood transfusion, or during a miscarriage, abortion, or after the delivery of a child, when the baby’s blood mixes with the mother’s. It can also happen during pregnancy, as the baby’s blood can cross the placenta and come in contact with the mother’s. If the mother’s platelet type is negative for a certain antigen and the baby’s platelets are positive for that antigen, the mother may form antibodies against the baby’s platelets.

During pregnancy, these antibodies cross the placenta (afterbirth) and attach to the platelets in the baby’s blood.

The antibodies can cause the unborn baby’s platelets to disappear from his or her blood stream, resulting in a low platelet count. This is called thrombocytopenia. The disease process that happens in the fetus or baby is known as Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia. It is a direct result of the platelet alloimmunization in the mother. In about one fourth of cases, the baby can experience spontaneous bleeding into the brain; in about one third of these cases, this leads to fetal death.

2. Can platelet alloimmunization and Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia be prevented?

No, there is currently no medication to prevent the development of platelet antibodies.

3. How common is platelet alloimmunization and Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia?

Studies of a large number of women have shown that about one in every 1000 women who are HPA-1 negative have antibodies. About 10% of HPA-1 negative women who have previously given birth to a HPA-1 positive child, have antibodies. Intracranial haemorrhage due to neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia occurs in about one out of every 10,000 deliveries. 2020

4. Does platelet alloimmunization cause repeated early miscarriages?

Platelet antibodies do not begin to cross to the unborn child until approximately ten weeks of pregnancy.

Note: Latest research indicates that FNAIT is implicated in repeated early miscarriage and Intrauterine Growth Restriction.

5. How is Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia diagnosed?

There is no routine blood test that is performed in pregnancy to see if a mother has antibodies to platelets. Most mothers do not even know they have this disease unless they give birth to a baby with a low platelet count or if their sister gives birth to an affected baby.

Physicians take several steps to diagnose this disease. They can:

- Check the mother’s platelet type

- Check the father’s platelet type

- Check the mother’s blood for antibodies

- Perform an amniocentesis (the process of getting a fluid sample from the amniotic sac) to check the baby’s platelet type

- Perform several ultrasounds

- If necessary, conduct a cordocentesis (the process of getting a blood sample from the unborn baby’s umbilical cord) for more information.

* See Important Note for cordocentesis at the end of this section.

Checking the Mother’s Platelet Type

One of the first steps in finding out whether platelet alloimmunization is present is to check the mother’s platelet type. This involves drawing a special blood sample and sending it to a reference laboratory. If the mother is HPA-1 negative, the test result will return HPA-1b/1b.

Checking the Father’s Platelet Type

The father of a previously affected fetus or neonate should also undergo platelet typing. Again, this involves drawing a special blood sample and sending it to a reference laboratory usually along with the mother’s blood sample. If the father is HPA-1 positive, his result can return in one of two ways. He may be determined to be HPA-1a/1a. In this case he is called “homozygous” and all of his offspring with an HPA-1 negative partner can develop a low platelet count. This situation occurs in about 75% of individuals that are HPA-1 positive. If his results return HPA-1a/1b, he is called “heterozygous”. This situation occurs in about 25% of individuals that are HPA-1 positive. This means that only half of his offspring can inherit the HPA-1a antigen. This occurs by chance, like a roll of the dice, when the sperm and egg meet. If the fetus inherits the HPA-1a antigen, it can develop a low platelet count.

Check for Maternal Antibodies

When platelet typing is performed on the baby’s parents, another sample of blood is usually taken from the mother to see if she has antibodies to her partner’s platelets. However, the level of antibody in the mother’s blood cannot predict the chance of a baby developing thrombocytopenia or experiencing bleeding. Often a “mixing study” is also done as part of the evaluation of the couple. In this case, the liquid part of the mother’s blood is put in the same tube as her partner’s platelets to see if there are antibodies present that will attack them.

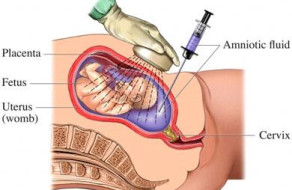

Amniocentesis

If the father is heterozygous for the platelet antigen, the baby’s platelet type can be determined through amniocentesis. This is done by testing a sample of amniotic fluid, the fluid that surrounds the baby inside the womb. This procedure is usually done after about 15 weeks of pregnancy. With the aid of ultrasound, a needle is guided through the mother’s abdomen (stomach) and into the amniotic sac (bag of water) around the baby (sees Diagram 2). A small amount of fluid is withdrawn and tested to determine the baby’s platelet type. In about half of cases, the baby will be found to HPA-1 negative and there will be no further concerns in the pregnancy. There is a small level of risk involved in amniocentesis; loss of the fetus (baby) occurs in about one in 800 procedures.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound cannot be used to detect a low platelet count while a baby is still in the womb. However, ultrasound can be used to look at the baby’s brain for evidence of bleeding.

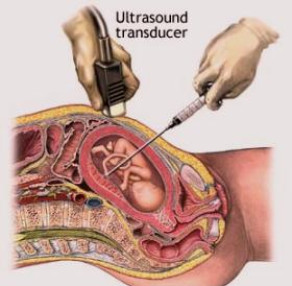

Cordocentesis – also called fetal blood sampling or percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS)

Cordocentesis can also help provide information about a baby’s platelet level. This procedure is very much like amniocentesis, except that instead of inserting a needle into the bag of water around the baby, it is placed into the umbilical cord to get a sample of blood. This test directly measures the amount of platelets in the baby’s blood.

Important note:

The use of cordocentesis in alloimmune thrombocytopenia is controversial. Many maternal-fetal medicine specialists are reluctant to perform cordocentesis as a low platelet count in the baby can cause significant bleeding from the umbilical cord and other complications at the time of the procedure.

Currently belief is that fetal blood sampling should be reserved for patients who are interested in having a vaginal delivery. In those cases, the procedure would be performed after 32 weeks of gestation to document that the fetal platelet response to therapy has been adequate enough to safely permit a vaginal delivery to occur, and late enough in gestation to deliver a viable newborn if any complications occur. If fetal blood sampling is to be performed, the following is recommended: an experienced operator, use of a small-diameter sampling needle (22-gauge), performance in an operating room setting in the event that an emergent delivery is required, immediate access to an automated hemocytometer so that a rapid platelet count can be obtained (preferably available in the operating room), and the availability of antigen negative platelets for transfusion if the fetal platelet count is less than 50,000 mm3.

6. How is Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia treated during pregnancy?

In an effort to prevent a low platelet count in the baby, a medication called intravenous immune globulin is often prescribed. This medication is made from antibodies from many people. The exact way that intravenous immune globulin prevents thrombocytopenia in the baby is unknown. It may cause the mother to make less anti-platelet antibodies, it may block her antibodies from crossing the placenta (afterbirth) to get to the fetus or it may prevent the platelets in the fetus that have antibodies attached to them from being destroyed.

The major side effects of this medicine appear to be severe headache, nausea and rash. Patients may take two extra-strength acetaminophen tablets (Tylenol®) and an anti-histamine (Benadryl) before receiving intravenous immune globulin. Typically the first one or two doses are given in the hospital over six to eight hours. Subsequent doses are given weekly and can be administered by a home health care agency. Intravenous immune globulin is very expensive, however most insurance companies pay for its use in Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia after it has been pre-approved.

(Note: Medication brand names will differ according to country, as will treatment costs, place and time taken for IVIG administration.)

The dose and the timing for the start the intravenous immune globulin typically depend on how severely a previous child was affected by Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia.

- If a previous child had only a low platelet count after birth, then intravenous immune globulin is usually started at a low dose (usually one gram/kilogram of maternal body weight) at 20 weeks of the pregnancy. This is repeated weekly. At around 32 weeks into the pregnancy, prednisone, a steroid pill that is taken by mouth, may be added. This medication is usually taken once or twice daily. Prednisone is usually well-tolerated, although it can be associated with diabetes in pregnancy, weight gain, mood changes and an increase in appetite.

- If a previous unborn child had bleeding into the brain before seven months of pregnancy, then intravenous immune globulin is started as early as 10 weeks of pregnancy at a higher dose (two grams per kilogram of body weight). The dose is usually given over two separate days to reduce the rate of complications; this is repeatedly weekly. Prednisone is usually added at around 20 weeks of the pregnancy.

- If bleeding occurred into the brain of a previous unborn child after seven months of the pregnancy and before 36 weeks’ gestation, intravenous immune globulin is usually started by 12 weeks of pregnancy at a dose of one gram/kilogram and repeated weekly. Prednisone is added at around 20 weeks and the dose of intravenous immune globulin is increased to two grams/kilogram at around 28 weeks of the pregnancy. The increase in the dose of intravenous immune globulin will required two infusions each week.

- If bleeding occurred into the brain of a previous unborn child after 36 weeks of the pregnancy or after the child was born, intravenous immune globulin (one gram/kilogram/week) is started at around 12 weeks of the pregnancy. At 24 weeks of gestation, the dose of intravenous immune globulin may be increased to two grams/kilogram/week OR prednisone may be prescribed.

Platelet transfusions to the baby in the womb are not typically used as the primary treatment for Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia is during pregnancy. Giving platelets to the unborn baby is associated with a risk of bleeding from puncture of the umbilical cord. In addition, platelets do not last more than seven to ten days in the baby once they are given.

Note: It is important to see your Fetal Maternal Medical specialists for current treatment protocols, and to put a treatment plan in place tailored to fit your particular NAIT history.

7. How is the end of a pregnancy complicated by NAIT managed?

Medications will be continued throughout the pregnancy. Most physicians will deliver a pregnancy complicated by Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia by 38 weeks (two weeks before the usual due date). One of two approaches can be taken:

- Cordocentesis can be performed with maternal platelets or antigen negative platelets from another donor available if the fetal platelet count is found to be low.

- If the fetal platelet count is found to be low (< 50,000/mm3), a cesarean section can be performed.

- If the fetal platelet count is found to be > 50,000/mm3, then an induction of labor can be undertaken to attempt a vaginal delivery. In this case, the delivery should be spontaneous and not assisted with forceps or vacuum extraction.

- Elective cesarean section is chosen by the majority of mothers for their delivery. Several days before the planned day of the delivery, the pregnant mother can undergo platelet-pheresis. In this procedure, a tube is placed into a vein and small amounts of the mother’s blood are sent into a special machine which will then remove the platelets. The liquid portion of her blood and red blood cells are then transferred back into her body. The platelets that were removed are negative for the antigen that has caused the problem, and they can then be used to treat the baby once it is born.

8. Will a baby need special attention after he or she is born?

Your baby will be watched very closely and his or her blood will be checked several times to measure the platelet count. If the count is low, the baby will receive platelets that were collected earlier, or will receive platelets from a special antigen negative donor person. In addition, if the baby’s first few platelet counts are low, he or she may need treatment with intravenous immune globulin or steroids (much like you received during pregnancy). Also, your baby may undergo a special ultrasound or MRI of the head to be sure that there was no bleeding into the brain. Typically, a baby at risk for Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia will remain in the hospital a little longer than usual.

9. Can I breastfeed my baby?

There is no reason why your baby cannot be breastfed. If the baby needs specialized treatment in the intensive care nursery, the mother may be asked to “pump” her breast to store the milk for later use. In any case, a lactation consultant can provide assistance.

10. Will my baby require any other treatment after it comes home?

Not usually. Once the baby is born, antibodies are no longer crossing over through the placenta to attach to his or her platelets. This means that the baby should be able to keep a normal platelet count.

If all initial testing is normal, the baby should not be at risk for any long term problems.

11. If my baby is a girl, can she experience platelet alloimmunization in a pregnancy later in life?

No. The reason your baby girl experienced Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia was that she was HPA-1 positive. This means that she cannot form antibodies to this particular platelet antigen later in her life. All of her offspring will not be affected by Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia no matter what partner she chooses.

12. If my partner is heterozygous for the HPA-1 gene and we have a girl who inherits the negative antigen from both of us, will her children be affected by Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia?

This is possible under two conditions: her partner will have to have the HPA-1 gene and she will have to develop antibodies to the antigen during a pregnancy.

13. Can I still donate my blood for others to use even though I am positive for platelet antibodies?

Since red blood cells that are stored after donation contain very little of the liquid portion of the blood that contains the antibodies, mothers with these antibodies should be able to donate blood. However, they should inform the blood donation center that their blood has antibodies to platelets.

The blood center may be interested in talking with you about becoming a special donor for platelets since you have a rare type of platelets found in only two out of every 100 patients. These platelets could be used for babies affected by Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia.

14. Do I need to be aware of my platelet type in case I am in need of a blood transfusion, and how do I make this known to a health care provider?

When a patient needs a blood transfusion after surgery or a car accident, usually red blood cells are all that are needed. In some extreme cases when there is a large amount of bleeding, a platelet transfusion is also required. In these cases, it would be important to let your health care provider know that you have antibodies to the most common type of platelets that would be used. Although it would be safe to use platelets from most donors, the antibodies in your blood could cause the platelets to disappear from your bloodstream before they can work to stop bleeding.

Many companies can make a customized medical alert bracelet to alert your health care provider of the presence of your platelet antibodies.

CONCLUSION

We hope this booklet has answered many of the questions that you or your family may have concerning Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia.

Kenneth J. Moise, Jr., MD. Copyright ©2010

http://www.texaschildrens.org/carecenters/FetalSurgery/Moise.aspx

References

1. Berkowitz RL, Bussel JB, McFarland JG. Alloimmune thrombocytopenia: State of the art 2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:907-13.

2. Bussel J. Diagnosis and management of the fetus and neonate with alloimmune thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7 Suppl 1:253-7.

3. Skogen B, Husebekk A, Killie MK, Kjeldsen-Kragh J. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia is not what it was: a lesson learned from a large prospective screening and intervention program. Scand J Immunol 2009;70:531-4.

4. Bussel JB, Berkowitz RL, Hung C, Kolb EA, Wissert M, Primiani A, Tsaur FW, MacFarland JG. Intracranial hemmorhage in alloimmune thrombocytopenia: stratified management to prevent recurrence in the subsequent pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:135.e1-14.